Stephen and Sandra Swanson were eating dinner beside their Christmas tree in 2017 when a Navy official rang the doorbell with alarming news: Hazardous chemicals from firefighting foam, used during training exercises at a nearby military airstrip, had seeped into their well water.

“We were told, ‘Don’t drink the water. … It’s toxic.’ Then we were handed bottled water from Safeway,” Stephen Swanson, a 78-year-old retired emergency room physician, said in an interview from his home on Whidbey Island, Wash. “It felt like a gut punch.”

Months later, Swanson provided the Washington state legislature with tests showing his blood was filled with high levels of contaminants found in the foam: per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly called PFAS or “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in the body or in nature.

His testimony helped convince the Democratic-controlled state legislature in 2018 to become the first in the nation to restrict the use of firefighting foam that contains the chemicals as well as PFAS-laced food packaging, which numerous studies have linked to cancer, infertility and a host of other diseases.

Since then, at least 106 similar laws have been enacted in 24 states, many with GOP-dominated legislatures, to ban or restrict the use of chemicals that are valued for their waterproof, stain-repelling, nonstick and fire-resistant properties and found in a vast array of everyday products including carpeting and rugs, outdoor apparel and stick-proof cookware.

This year alone, 195 new bills were introduced in dozens of state legislatures, seeking to require that an expanding list of products be PFAS-free. Some states have set deadlines that require all or most products made or sold in their states to be PFAS-free, with Minnesota the latest to pass such a measure last month.

The chemical industry argues that the tide of new legislation is a gross overreaction and that the majority of PFAS chemicals are safe. But the laws have received rare bipartisan support in an era when political divides have deepened in state legislatures, helped by lobbying pushes from broadly popular groups such as firefighters and farmers, and have prompted major companies like McDonald’s, Ikea and Target to set deadlines for eliminating PFAS chemicals in all or most of their products.

“By 2025, these state laws are going to reach a critical mass, and every industry is going to have to face what these other companies have already faced,” said John Gardella, a Boston-based lawyer who represents many of the companies and industries that use the chemicals.

This boom in state-level bans comes as federal regulators have lagged for decades on taking action. While the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry says the threat of long-term PFAS exposure is not fully known, activists and medical experts point to mounting evidence suggesting the chemicals are linked to liver and immune system damage, as well as other risks. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in March proposed for the first time a rule to set legally enforceable limits nationwide on six forever chemicals, although the regulations would cover only water contamination.

After decades of denying that any PFAS chemicals are hazardous, the American Chemistry Council, the industry’s primary trade group, now says at least two of the substances could be problematic at high levels. But the group also argues that the vast majority of the 5,000-plus chemicals in the group are safe and that states are going too far by banning or restricting all of them. The group also says the laws could block production of important products, such as semiconductors and medical devices.

“We have strong concerns with overly broad state legislation that takes a one-size-fits-all approach to the regulation of these chemistries,” said Robert Simon, a vice president with the American Chemistry Council. “Furthermore, a patchwork of conflicting state-based approaches could jeopardize access to important products.”

Simon’s group has asked the federal government to set national standards but has also successfully fought congressional bills to restrict PFAS, including some legislation that died earlier this year, which the group argued went too far by restricting many chemicals the industry says are safe.

State lawmakers who have backed the bills say they’ve fought for broader PFAS bans because new versions of potentially dangerous PFAS chemicals are regularly introduced into the market. Following the industry’s advice would trigger a “whack-a-mole” situation, they say, forcing legislators to pass new laws each time a new PFAS chemical is developed.

The EPA said that its newly proposed ban on two chemicals and restrictions on four others are based on reviews of hundreds of scientific studies showing links to a variety of health problems and are focused on PFAS that can be reliably detected in water and for which there are “proven treatment technologies.” The agency noted that it’s continuing research on other PFAS chemicals and considering further regulations, enforcement actions and technologies that can remove them from the air, land and water.

Until the EPA and other federal agencies do set stricter policies on PFAS use in products and start levying fines to violators, some lawmakers say, state laws are the only recourse.

“What often happens when the federal government fails to act, states step in because we have to protect our citizens,” said Maryland state Del. Sara Love (D-Montgomery), who sponsored a bill signed into law last year that bans forever chemicals in firefighting gear and other products. “We also know that the more states that passed legislation on this, the more it would really push the federal government to do something.”

Forever chemicals were invented in the 1930s and a decade later went to market in nonstick and waterproof coatings in cookware and clothing. By the 1960s, their unique resistance to water, oil and stains prompted a variety of industries to start using the substances, including in firefighting foam and electronics.

The health risks first received widespread notice in 2001, when attorney Robert Bilott sent a 19-page open letter detailing potential hazards and asking the EPA to investigate the disposal of the chemicals by E.I. du Pont de Nemours, commonly referred to as DuPont.

Five months later, Bilott filed a class-action lawsuit against DuPont. A settlement agreement in 2004 awarded affected residents $70 million in damages and created a scientific panel that reviewed existing research and conducted new studies on PFAS exposure, while also testing 69,000 people near a DuPont site in the Mid-Ohio Valley in West Virginia.

The panel released a series of reports in 2011 and 2012 that determined there were probable links from PFAS exposure to kidney and testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, pregnancy-induced hypertension and high cholesterol. More than 3,500 of the people tested were later diagnosed with one of the linked diseases.

At the time, DuPont argued the chemical in the study — which it has since phased out — was safe and denied any wrongdoing in the settlement agreement. In response to the panel’s reports, the company in some instances said it did not believe there was a link to health problems and in other instances emphasized reforms it had undertaken, such as the installation of water-filtration systems.

Today, “the company’s use of PFAS is limited,” according to DuPont’s website. “We have systems, processes and protocols in place ensuring that PFAS is used safely, controlled to the highest standards and minimized.”

The EPA also sued DuPont in 2004 for violations of the Toxic Substances Control Act and settled with the company the following year for $16.5 million. Following the release of the panel’s scientific studies, the EPA began testing drinking water at sites across the country, revealing widespread contamination in 27 states that affected 15 million people. The Defense Department followed in 2016, checking water around its military bases and finding it, too, contained PFAS chemicals.

“This information bubbled up to the state legislatures, with state legislators taking notice that their districts were contaminated and grass-roots environmental groups forming to try to address the issue,” said Melanie Benesh, vice president of the Environmental Working Group, which in 2016 first released its map that pinpoints the locations of all the contaminated sites. The map now shows contamination in all 50 states, with about 200 million Americans potentially affected.

The possible health impact of exposure to the chemicals is still a subject of medical study. The EPA recently calculated that restricting six PFAS chemicals in water supplies could have a measurable impact on heart disease alone, preventing 6,000 nonfatal heart attacks, more than 8,800 strokes and 754 deaths. Another peer-reviewed study by Harvard and Chinese-based researchers determined that exposure to one PFAS chemical was associated with 382,000 deaths annually in the United States from 1999 to 2015.

In 2017, bills were introduced in nine state legislatures to ban the chemicals in certain products, with Vermont the first to pass a narrow restriction on one PFAS chemical tied to a single contamination site.

The number of bills quickly rose the following year to 38, with four passing, beginning with Washington state, the first with a broad ban on the entire class of PFAS chemicals in products, beginning with firefighting foam and food packaging.

Similar proposals have increased exponentially ever since, with a record high of 245 bills introduced last year. Two documentaries and the 2019 film “Dark Waters” starring Mark Ruffalo, about Bilott’s fight with DuPont, helped fuel the state legislative movement. (Bilott also wrote about the legal battle in his book “Exposure.”)

In an interview with The Washington Post, Ruffalo credited the film with dispelling myths that poor diets or farming practices had caused the health problems highlighted by Bilott’s suit.

“There is a lot of shame around illness. It showed them it wasn’t them,” Ruffalo said. “It wasn’t their fault. It was done to them, and it was done knowingly.”

Ruffalo said the movie also helped to mobilize victims — along with firefighters and grass-roots environmental groups — to push state lawmakers to take action.

“It’s a case study in the power of film, and it is really what storytelling is all about,” he said. “It is about reaching people where they are. It humanizes us. It humanizes the issue. And it transcends political bounds.”

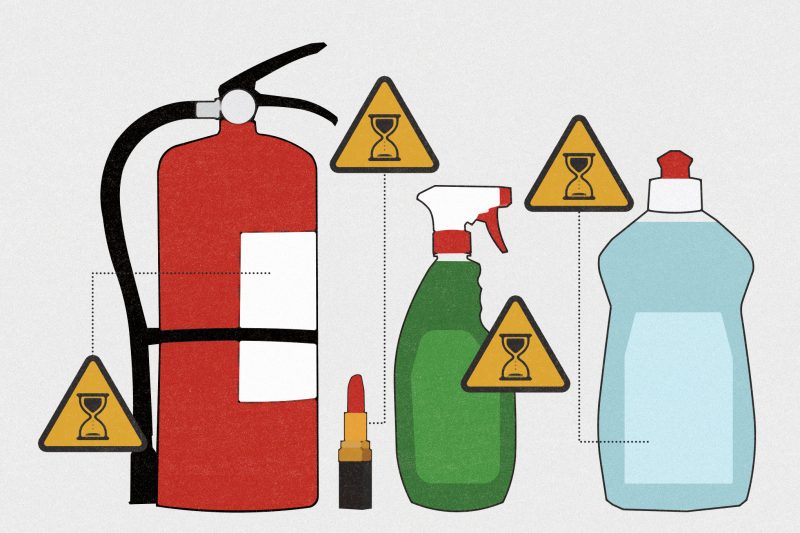

As the number of state bills have grown, so too has the list of products they are seeking to make PFAS-free, including cookware, surf and ski wax, artificial turf, carpeting, rugs, furniture, outdoor apparel, cosmetics and menstrual products.

Ten states have implemented drinking-water standards with various PFAS limits well below the only existing national standard — a nonenforceable 2016 guideline from the EPA. The agency’s new regulation proposed in March would put legally binding limits of 4 parts per trillion or less on six PFAS chemicals in drinking water, nearly 18 times less than the current guideline. The public comment period for the proposed rule closed May 30, and it could go into effect as soon as December.

“When you had multiple states setting drinking-water standards, that absolutely was part of the pressure that pushed the federal government to finally act,” said Sarah Doll, national director of Safer States, a coalition of environmental health groups focused on toxic chemicals that tracks PFAS legislation.

In other state actions, attorneys general in 17 states have also filed lawsuits to force companies that have produced or used forever chemicals to finance cleanup efforts and to provide medical monitoring to people with high PFAS levels in their bloodstreams.

Companies that make products using PFAS have argued they are not liable, since they didn’t manufacture the substances. And many of the companies that make forever chemicals say their prevalence makes it difficult to pinpoint them as the source of health risks.

Several states have started to move beyond a product-by-product ban of the chemicals to more sweeping laws that set deadlines for removing PFAS from all products, with a few caveats. In 2021, Maine became the first state to do so. The law, which takes effect in 2030, bans any intentionally added PFAS in products. However, if there is not yet a PFAS-free alternative, it allows for exceptions in products deemed to be “essential for health, safety or the functioning of society.”

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz (D) signed a similar bill last month, setting a deadline for some products to be made without the chemicals by 2025, with others facing a 2032 deadline.

In 2019, the Washington legislature ordered the state Department of Ecology to seek PFAS-free alternatives for a variety of products and then set phaseout deadlines. Last year, legislators expanded the scope of the rule and set a 2025 deadline for some products, including apparel and cookware.

“We were able to speed up the timeline for eliminating PFAS, and it was a big fight,” said state Rep. Liz Berry (D). “The chemical companies and their lobbying efforts were very strong.”

Gardella, the Boston-based attorney who represents many of the affected companies, said the new laws will be difficult to follow since many products made in the United States use materials from overseas.

“These components and chemicals don’t always come in containers that say ‘PFAS,’ right?” Gardella said. “When companies ask if they contain PFAS, they’ll get a response that’s very vague, like, ‘This component that we sell has no hazardous substances in it.’ Okay. That’s nice, but who’s determining that?”

Some companies that are going PFAS-free are pledging to play a more active role in keeping the chemicals from their products. McDonald’s said it is now conducting its own “robust testing for chemicals” with the goal of using PFAS-free food packaging by 2025.

Simon, with the American Chemistry Council, said that many modern-day PFAS compounds are safe and made of shorter chemical chains, which allows them to break down more easily than older versions of the man-made chemicals. “Newer PFAS chemistries are eliminated from the body more quickly and do not accumulate in the body like the legacy products,” Simon said.

However, critics point to a 2020 peer-reviewed study by a team of scientists at Auburn University that found the short-chain PFAS compounds are “more widely detected, more persistent and mobile in aquatic systems, and thus may pose more risks on the human and ecosystem health” than their long-chain predecessors. The EPA made similar determinations the following year.

Simon’s group disputes that the studies conclusively prove that modern PFAS are as significant a health threat. Simon also said that many products — crucial to everyday life — cannot be made without the use of PFAS. As state laws become more aggressive, he said, it may lead to a shortage of medical devices and semiconductors key for smartphones and computers.

Benesh, with the Environmental Working Group, said that even though important products cannot yet be made PFAS-free, the industry could be doing more to protect the public.

“They should be capturing PFAS in their production processes, they should be filtering their wastewater, and they should be monitoring the release of PFAS into the air and water so they aren’t making this problem any worse,” she said.

Lawsuits against the makers and users of PFAS chemicals have snowballed since Bilott’s original lawsuit, as have the size of the settlements. Last week, DuPont de Nemours Inc. and other companies announced a $1.185 billion settlement over pollution claims tied to the manufacture of the compounds.

Environmentalists are now pushing states to regulate another source of PFAS contamination — sewage sludge, which is widely used as fertilizer on cropland in all but two states. For decades, municipal sewer districts have partnered with farmers as a cheap and reliable way of disposing of the waste.

Connecticut has long banned use of the bio-waste as fertilizer over a variety of environmental concerns, and in 2021, Maine became the first, and so far the only, state to ban its use specifically due to PFAS contamination.

The move came after the state started testing groundwater on farms that were treated with the sludge, which is filled with human and industrial waste. State officials also put out a map of all the sludge-treated sites that contained high levels of PFAS in their groundwater, which included Fred Stone’s dairy farm.

“The map makes the state of Maine look like it has smallpox — it’s that prevalent,” said Stone, who had to close his dairy farm in Maine because of the contamination in his cows’ milk. “If I was operating in most any other state, I’d still be shipping my milk — and that should scare the bejesus out of everyone.”

Alice Crites and Magda Jean-Louis contributed to this report.