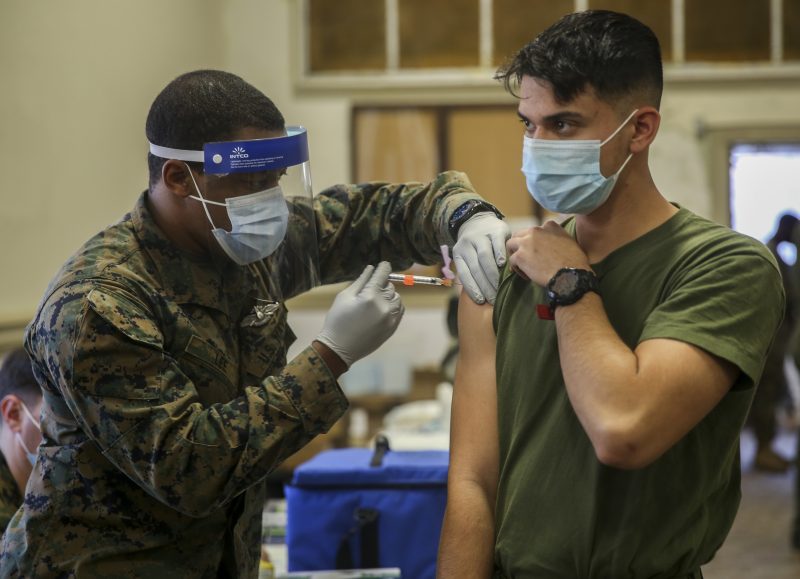

Congress is poised to force the Pentagon to end the military’s coronavirus vaccine mandate under compromise legislation to authorize funding for the Defense Department, a major capitulation for Democrats who championed the policy despite sharp controversy in the ranks over its implementation.

The abrupt termination of the requirement, which became Pentagon policy in August 2021, came after Republican lawmakers threatened to stymie action on the $858 billion bill. It was incorporated into the legislation in apparent defiance of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who “supports maintaining the vaccine mandate,” Pentagon press secretary Brig. Gen. Patrick Ryder said this week, adding, “The health and readiness of our forces is critical to our warfighting capability and a top priority.”

Yet Republicans who championed the repeal were quick to label it a first step, calling on the Biden administration to reenlist service members discharged under the policy.

“Make no mistake: this is a win for our military,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) said in a statement late Tuesday night, warning that when the GOP takes over the House next year, Republicans will “work to finally hold the Biden administration accountable and assist the men and women in uniform who were unfairly targeted.”

While the decision to roll back the vaccine mandate was politically divisive, freezing negotiations between Republicans and Democrats on the House and Senate armed services committees for several days, it is far from the only Pentagon policy challenged in the compromise defense bill. The measure, which the full House and Senate still must vote to approve, pushes the Defense Department and related agencies to adopt several ventures, including new programs to arm Taiwan and scrutinize military assistance to Ukraine, and retain aging weapons systems the Biden administration has slated for decommissioning.

The bill creates several new accountability measures for the billions of dollars in military assistance being sent to Ukraine. Those include ordering reports from the Defense Department and a consortium of inspectors general about the methods being employed to track weapons, with the aim of identifying potential shortfalls.

While enhanced oversight of Ukraine aid has become a rallying cry for Republicans skeptical of the continued provision of advanced systems and munitions, the measures included in the defense bill had earlier secured bipartisan support in the House. The Senate never voted on its version of the bill before the compromise legislation’s unveiling.

The bill creates new pots of funding to underwrite training and weapons purchases for Taiwan, which faces increasing threats to its independence from China, and approves the island for presidential drawdown authority — a program that enables the United States to send weapons from its stocks to U.S. allies. The Biden administration has leaned on the tool heavily in its efforts to keep Ukraine armed in its fight against Russia.

The bill would dedicate $1 billion in presidential drawdown authority for Taiwan annually over five years, plus $2 billion per year in grant assistance for training and weapons purchases. Those sums would put Taiwan behind only Israel in terms of the military aid it receives on an annual basis.

The effort gained more momentum from lawmakers who, aghast at Russia’s assault on Ukraine, hoped to prevent a similar situation from manifesting between China and Taiwan. Tensions over Taiwan reached a fever pitch during negotiations this summer, after Beijing reacted to a visit by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) by canceling diplomatic engagements with the United States and launching missiles over the waters around Taiwan. Such tensions have calmed a bit in recent weeks, as President Biden and his top national security advisers have held direct talks with their Chinese counterparts on the sidelines of international confabs.

The Taiwan provisions, according to congressional aides, were crafted with White House input. But the defense bill resists other changes the administration has tried to make to the U.S. arsenal amid fresh challenges from China and other rival nations, particularly in the realm of nuclear weapons.

Earlier this year, the Pentagon announced it would retire two classes of nuclear arms it deemed superfluous: the megaton-plus capacity B83-1 gravity bomb and the tactical submarine-launched cruise missile known as the SLCM-N. The defense bill keeps a pot of $25 million on hand for continued research into the SLCM-N system, and “limits retirement” of the B83-1 “until a suitable replacement capability for defeating hard and deeply buried targets can be identified,” according to a summary of the legislation.

The House is expected to pass the measure Wednesday, setting up a vote in the Senate that would send the measure to Biden for final approval — and maintain a six-decade long tradition of Congress passing defense authorization bills, even when other parts of the federal government failed to receive such focused consideration.

But the new programs may not come online for some time. Lawmakers have yet to reach a deal to fund the government with a budget bill that would take all of the authorized measures into account. And as the deadline looms — the current federal budget expires Dec. 16 — Congress may have to pass a short-term spending measure to avert a government shutdown before the holidays, as Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) predicted Tuesday.