Eleanor Jackson Piel, a lawyer who doggedly pursued civil rights and civil liberties cases, cleared the name of a man who had spent 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit, and obtained a stay of execution for two death-row inmates 16 hours before they were to be electrocuted, later helping win their release, died Nov. 26 in Austin. She was 102.

She had a neurodegenerative disease, said her daughter, Eleanor Womack, in whose home Ms. Piel died.

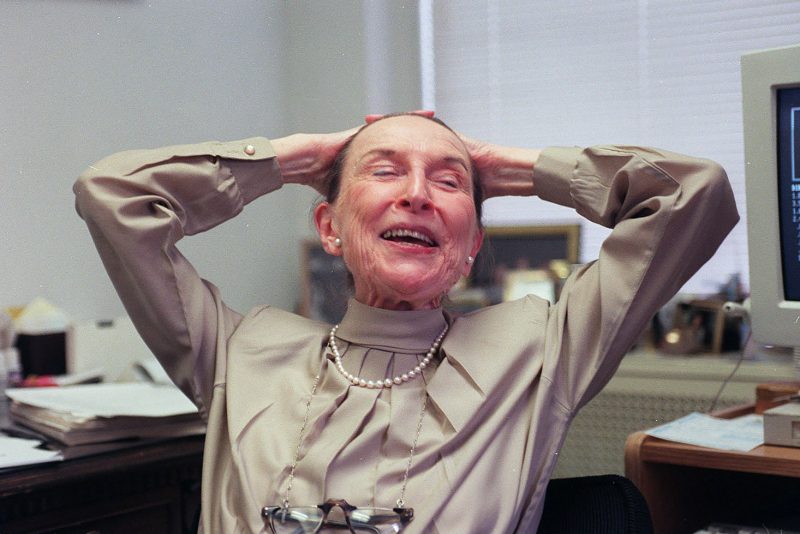

Ms. Piel, one of exceedingly few women in her generation to enter criminal law, practiced into her 90s, attracting a national reputation as an unrelenting advocate for her clients. But as she set out on her career, she was told she held no promise at all.

When she applied to law school in 1940, she was turned away from the University of California at Berkeley because the acting dean was of the opinion that “females always had nervous breakdowns.” She later gained admission as a transfer student — and as the only woman in her graduating class.

As a young lawyer, she discovered that law firms had little interest in hiring female counsel. She turned their rejections to her advantage, starting a private practice, based first in Los Angeles and then in New York, which allowed her to take cases on her own terms.

“I am persistent,” she told the New York Times, “and I like to challenge authority. No question about it.”

Female lawyers of Ms. Piel’s era were generally limited to the handling of divorces, trusts and estates, and other matters of family law. As a woman practicing in the criminal field, Ms. Piel had “no role models,” Linda Greenhouse, a lecturer at Yale Law School and a longtime U.S. Supreme Court reporter for the Times, said in an interview. “She really kind of invented herself by going into that line of work.”

“Criminal law was such a low level in the profession that anyone who gave it time was a sport,” Ms. Piel told the Times. “I couldn’t understand why it was so disrespected. To me, facing the unknown and coming up with something on my feet that worked was heaven.”

At times, Ms. Piel was refused access to male clients in jail because she was a woman. Once, after she delivered a closing argument, a federal judge admonished the jury not to be swayed by her beauty.

Sometimes the indignities accumulated to such a degree that even Ms. Piel — once described by the Times as “the courts’ most elegant pain in the neck” — lost her equanimity. On one occasion, a man introduced her at a party as “the best woman lawyer in Los Angeles.” Offended by what she considered the gratuitous reference to her sex, she punched him.

Although perhaps best known for her criminal practice, Ms. Piel took a wide range of cases over her decades in law. Early in her career, she worked on behalf of Japanese Americans interned by the U.S. government during World War II.

In a civil suit in the 1960s, she represented a White teacher, Sandra Adickes, who had been arrested for vagrancy after trying to dine with six Black students at a segregated Kress lunch counter in Mississippi in 1964. In one of four cases that Ms. Piel argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, she won a judgment in her client’s favor and ultimately settled out of court.

Later that decade, Ms. Piel represented Alice de Rivera, a high-achieving 13-year-old student who filed a suit to be granted admission to Stuyvesant High School in New York, a prestigious public school then restricted to boys. Girls were admitted in 1969, although by that time Rivera had moved.

Ms. Piel achieved one of her most noted successes in 1988, when she helped secure the release of two half-brothers, William Riley Jent and Earnest Lee Miller, convicted in the 1979 murder of a Florida woman who had been strangled and set on fire. Her body, disfigured beyond recognition, was discovered in a game preserve 60 miles from Tampa.

Because the victim was not yet unidentified, police and prosecutors were left “to solve the case by conjuring their own murder story out of thin air,” Ms. Piel later reflected in an essay about the case. They made what she described as an “arbitrary choice of defendants,” plucking Jent, a 28-year-old biker, and Miller, 23, a high school dropout who had gone AWOL from the Marine Corps, as two “available and disposable young men” to charge with the crime.

Known as the Death Row Brothers, the defendants were convicted in separate trials and received the death penalty. On their appeal, Ms. Piel represented Jent. A colleague, Howardene Garrett, represented Miller. Their work helped reveal the case to be what a 1985 investigation in The Washington Post described as “the most dubious death row conviction in Florida” at the time.

Among other problems, the victim was not conclusively identified until 1985, more than five years after the defendants were condemned. The family of the woman, Linda Gale Bradshaw, believed her to have been killed by a boyfriend, not by the convicted defendants. Critical witnesses offered shifting accounts, and investigators declined to pursue basic leads.

In 1983, Ms. Piel persuaded a judge to issue a stay in their execution 16 hours before the defendants were set to die in the electric chair. In 1988, they were freed after agreeing to a deal in which they entered guilty pleas for second-degree murder — although they maintained their innocence — and were sentenced to time already served with time off for good behavior.

“I’m happy for Bill and Ernie today because they are alive,” Ms. Piel said at the time, “but the taste is bitter because the price was a lie.”

The case of the Death Row Brothers “vividly illustrates one of the principal hazards to the administration of justice that arise from the acceptance of the death penalty in our law and custom,” Ms. Piel wrote. “That is the extreme behavior, in violation of their public trust, to which prosecutors and police are drawn by ambition and by the [attention] they can win by securing a death penalty.”

Eleanor Virden Jackson was born in Santa Monica, Calif., on Sept. 22, 1920. Her father, a physician, was a Lithuanian Jew who had changed the family name from Koussevitzky to Jackson when he immigrated to the United States. (The conductor Serge Koussevitzky was a relative.)

Ms. Piel’s mother, a concert pianist, was Protestant and discouraged Ms. Piel from acknowledging her Jewish ancestry. Ms. Piel was deeply affected by the experience of her father amid the prevailing antisemitism of the time, including his expulsion from a Santa Monica beach club when other members discovered he was a Jew.

“I was upset about the fact that people didn’t like Jews, when I was half Jewish, and then I had my mother being antisemitic,” Ms. Piel told a publication of Berkeley’s law school. “It just didn’t seem fair.”

Ms. Piel studied at the University of California at Los Angeles before graduating from UC-Berkeley in 1940. Turned away from Berkeley’s law school, she attended the University of Southern California, where she made law review before returning to Berkeley. She graduated in 1943.

After law school, Ms. Piel clerked for Judge Louis E. Goodman of the federal district court in San Francisco. He hired her for the job traditionally filled by recent graduates, she said, because “he thought if he had a woman she would stay there forever.”

The assignment proved immensely fulfilling, however, when Goodman was assigned to preside over United States v. Masaaki Kuwabara, a case involving 27 individuals who, like thousands of Japanese and Japanese Americans, had been incarcerated in internment camps during World War II. The individuals in the case had been arraigned after not reporting for the draft.

Working with Goodman, Ms. Piel found grounds to support a decision against the government. The 1940 Selective Training and Service Act declared that “in a free society the obligations and privileges of military training and service should be shared generally in accordance with a fair and just system of selective compulsory military training and service.” Detained as they had been, the internees, Goodman found, had scarcely been enjoying the benefits of a “free society.”

Ms. Piel later worked in Tokyo on the war crimes trials of Japanese officials as well as on the reconstruction of the Japanese economy. In 1948, she opened her law practice.

Ms. Piel was married in 1955 to Gerard Piel, the publisher of Scientific American magazine and a member of the family that made Piels beer. He died in 2004.

Besides her daughter, survivors include a stepson, Jonathan Piel of New York City; 11 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. Another stepson, Samuel Piel, died in 1965.

Ms. Piel was 78 years old when she secured one of her most rewarding judgments. It came in the case of Warith Habib Abdal, previously known as Vincent H. Jenkins, who had been convicted in 1983 of a rape in Buffalo. Ms. Piel had represented him in a manslaughter case the previous decade and worked on his appeal in the rape case with Barry Scheck, a co-founder of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit founded to guard against wrongful convictions.

On Ms. Piel’s insistence, DNA evidence was analyzed and reanalyzed — and ultimately showed that the defendant’s DNA did not match the assailant’s. He was released in 1999, 17 years after he had gone to prison on the charge.

“It’s hard to tell how I feel,” he told the Times when he was released, “because your heart is like your toe. It grows skin on it and it gets hard.”

“But,” he continued, “people like Mrs. Piel soften it up.”